Data science is not a backup plan: Advice for academics thinking about industry

Disclaimer: This is subjective advice, as is all advice. What worked for me may not work for you. Anyone offering to give you tips that guarantee success if you pay them is almost definitely a grifter.

If you’re an academic questioning whether you want to stay on the same path, you can’t just think of industry as a backup anymore. I think that ship sailed sometime in the mid 2010s. It is unfortunately a pervasive thought pattern among academics, and it’s 100% wrong. Hiring standards are high and the candidate-role fit is more important than ever. With widespread ML applications, the requirements for technical proficiency are also increasing non-linearly relative to academia.

I’m not saying this to dissuade you. I’m saying this to motivate you. There are lots of us who managed the switch, so you can too.

This is a heftier post. It’s based on my experience of finding a path to data science broadly construed from cognitive neuroscience, so it will be heavily tailored toward this field and basic sciences more generally, but I imagine some of the advice generalizes to other roles with tweaks (e.g. product, UXR, research scientist roles). You can navigate to relevant sections here:

Why I’m writing this

Basic useful info

Part 0: Start within

Part 1: Set your mental filters

Part 2: Create a resume

Part 3: Upskill

Part 4: Apply, apply some more

Part 5: Let’s get existential

Why I’m writing this

About a year into my postdoc, I sat down to write a bridge grant that would fund a few more postdoc years and then a few years of research if I were to get a faculty position. The postdoc part went okay but my future research program felt impossible. I gratefully read other people’s grants, I talked to my advisors, but the empty page kept glaring at me. I could come up with stuff but it wasn’t exciting stuff. It wasn’t stuff I felt I could build a cohesive research program and rally an engaged, motivated team around. I had no specific aims, I had no non-specific aims. Eventually, my nebulous and annoying discomfort took the shape of a realization: I was done. I had reached the end of my path and trying to go beyond this point wasn’t going to work.

I may at some point write a separate post on the process and benefits of learning that you need to pivot, but for now let’s just focus on the experience of figuring out what to do, and how to do it.

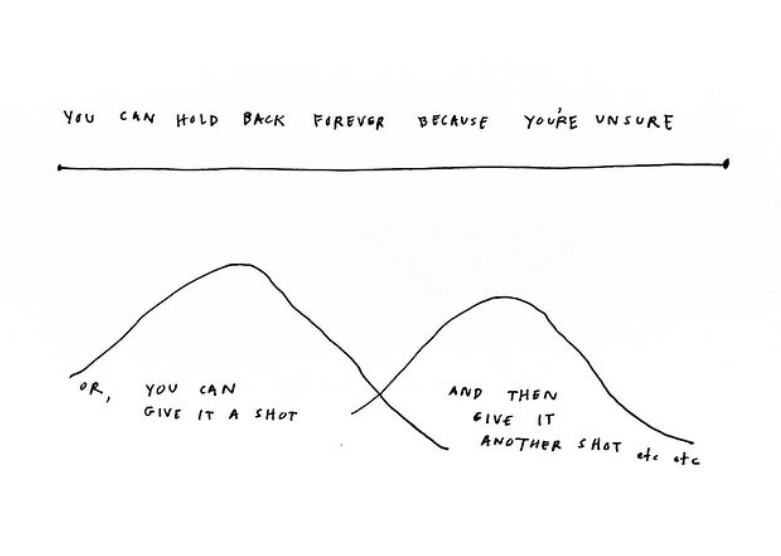

Unfortunately I don’t think there’s a way to avoid just doing things and learning from them, but almost 4 years later, I think I have some potentially useful advice to share with those thinking about the jump from academia to industry, and I wanted to put it in one place. Some of this advice is things I’ve done and thought worked well, some of it are post-hoc realizations after mistakes were made.

As the number of PhDs increases while the number of faculty positions stubbornly hovers at replacement-ish levels, I’ve observed a steady proliferation of coaches, mentors, advice-givers writ large with often very limited industry experience but all the answers. Ironically, the thing they’re most qualified to advise on is on how to become an alt-academic influencer. While I can imagine that someone hearing about your specific situation can provide slightly more tailored advice, I can’t see how the fundamentals of the process would change. I’m not going to go on a longer rant about grifting and gate-keeping, but I could (and have, as my long-suffering partner can attest to).

Okay, off my soapbox.

A word on data science nomenclature and levels

These boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred, but here’s my simple rule of thumb:

- Data analyst roles involve primarily writing SQL queries and building dashboards, typically with a focus on business insights. These roles don’t typically involve a ton of stats and are unlikely to involve any model building.

- ML/AI/applied scientist roles primarily involve building machine learning models and evaluating on standard ML metrics. These can focus on a bunch of different areas ranging from user journeys to revenue modeling, but all will require more knowledge of software engineering and cloud platforms like AWS and Google Cloud.

- Data scientist roles involve a blend of experimentation, statistics, and model building. A little bit of column A and a little bit of column B. In 2025, probably also LLMs. Inevitably, you will have to write some SQL and build a dashboard.

Most data science orgs follow broadly the same logic as software engineering levels:

The split between individual contributor and manager happens somewhere around the senior/staff level.

source.

source.

When you’re first applying from your PhD or postdoc, you might be at the more advanced tiers of ‘data scientist’ or early on in the ‘senior data scientist’ title range. I would say, though, that senior roles typically require industry experience even for those with PhDs. Some companies will specify exactly how they interpret the value of a degree, e.g. ‘1 year of experience in a similar role or a master’s degree’. Most will not, so it’s on you to make a case for yourself.

Part 0: Start within

It’s tempting to just set a LinkedIn alert for ‘data scientist’ and start applying to jobs that loosely encompass your existing set of skills.

If you have the privilege of time, however, I’d say don’t even open a job search engine until you have a basic idea of what you’re looking for. It’s easy to get stuck in a local minimum and not know it.

Write out the following lists:

- What do I like? Be specific. What about research do you like? Is it the statistics or is it talking to participants? Is it putting together powerpoint presentations with cool animations? It’s fine if your interests feel more low-brow than what you think ~being a scientist~ is. It doesn’t diminish your science or your intelligence if you realize what you really enjoy is communicating ideas simply rather than coming up with elegant experimental designs. Conversely, it doesn’t mean you have to stay in academia if what you enjoy is coming up with elegant experimental designs - it just means you need to look for a place where you can do what brings you meaning.

- What kind of feedback energizes me? Write out the kind of feedback that really made you feel seen and your work understood. Do you like people telling you I loved your paper or do you like hearing that was such a good talk? There may be complete overlap between whatever you put under point #1 and #2, and that’s fine - but there may be some differences too. To illustrate the contrast, I personally don’t enjoy crafting presentations nearly as much as I like data visualization, but I always feel the most proud when people tell me I gave a good talk, so a job with a heavier communication component is a good fit.

- What do I definitely not want to do? It’s extremely useful to have an ‘easy no’ category - where at most you read the first line of the job description before you scroll past it. This is the way you cull overwhelm and focus your search in a productive manner. What I mean here is a) cut out industries you morally oppose, and b) identify tasks you don’t enjoy. The latter is harder to come up with when you’ve only worked in academia. For me, it’s easy to say I don’t want to work on business insights, but unfortunately I only know this because I’ve worked in the field for long enough. It’s okay to keep your options completely open here. However, as you start looking at jobs and exploring your options, you will make your own life a lot easier if you start cutting things out as well.

You’ve gotten to know yourself a bit better. Now, it’s time to see what the lists you wrote coallesce around.

Part 1: Set your mental filters and talk to people

There are about 50 flavors of data science (I made that up, but you get it), and you probably aren’t interested in or well-suited to them all. For now, it’s fine to leave the job search general, but data science as a field has become a bit of a catch-all category, so it’s easy to become overwhelmed. This is where the other questions and your hard skills come into play.

Use the ‘easy no’ category as a clear boundary to keep your search streamlined. And now, you get to the fun part: use categories 1 and 2 as search sharpener tools.

Let’s take an example (not me):

- Primarily likes deep data exploration and modeling, iterating on a problem, would enjoy working as part of a team.

- Okay with giving presentations but doesn’t like dealing with squishy problems that require a lot of back and forth with non-technical people.

- Doesn’t like making dashboards.

- Most energizing feedback is someone called their code ‘elegant’.

There is probably a job exactly like this out there somewhere but it’s unlikely that any of us will get exactly what we want in life at any point in time. All jobs will have some level of cross-functional collaboration that will involve talking to non-data people. You will almost definitely have to stretch outside the strict bounds of your role. But, it can help you home in on things you should look out for. For our example scientist, here’s what actionable steps might look like:

- Focus on roles that are clearly embedded in data science teams/pods. This is much more common in larger, established corporations.

- Deprioritize roles that include a lot of cross-functional communication or roles where you’d be the only data scientist.

- Focus on roles that involve developing algorithms and building models. This can be gleaned from the job description. Be especially wary of ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ roles if you prefer working in a single focus area.

- Deprioritize roles with a heavy ‘analytics’ emphasis; these tend to involve more pulling of data from sql databases and putting together dashboards.

When I say deprioritize, I don’t mean never apply - these are not meant to be hard and fast rules. You may as well apply if your skillset fits well, and you might even be proven wrong in your self-assessment! But the goal is to make your search focused by applying mental filters. Now read through as many job listings as you can find with these mental filters on.

Once you’ve identified an industry/type of role you’re excited about, talk to people about it. You may already know someone (or multiple people) in your network who has made the switch. These are the first people you should talk to, because they’ll be more willing to talk off the cuff, even if what they do doesn’t sound that interesting to you. Candid info is the most valuable.

As you’re reading job listings, make a note of companies/roles that seem particularly exciting. Then, you can dig through the People tab on their company LinkedIn and try to see if anyone has a similar background to you and is now working in a related role. These are people I’d reach out to and ask if they were open to an informal chat. Especially in the early stages of job hunting, the primary goal should be learning more about their experiences and less about a specific job you found interesting - but don’t feel shy asking about the role, especially if they’re close to it.

The reason I recommend reaching out to people with a similar background is that they’re more likely to respond because they’ve gone through the same pain points as you. They will also be able to give you more useful advice because they have a better theory of mind for where your head is at this moment. It’s also a positive signal for the company’s hiring practices - if a company has hired people like you before, why not you? Keep the message short and nice, and don’t panic if they don’t reply and move on. People are busy and probably inundated with LinkedIn messages.

Part 2: Create a resume

Reading job descriptions before turning your academic CV into a resume will also help you learn the language and figure out how to translate your academic accomplishments into things recruiters and hiring managers understand.

You might have heard that a resume has to fit onto one page. When I first started applying to industry jobs, I crammed a ridiculous amount of information into a two-column, single-page resume. It was unreadable, cramped, and contained a lot of information I held on to because I was previously told it was important, but it didn’t actually matter much for the job I was trying to land. I don’t think the 1-page limit is true, and up to 2 pages is totally reasonable. That said, if it’s 2 pages and cramped, you’ve done something wrong (mine is now 1.5 pages with a comfortable amount of white space).

Resumes get parsed automatically by applicant tracking systems (ATS) at basically every company now, so the main thing you have to ensure is that it’s machine-readable. There are tons of websites that make you create an account and give you a score or similar nonsense. I like this open-source resume parser which doesn’t collect any data (you can even fork it on github!). Don’t overthink it, but always keep in mind the job you’re applying for. Put together a simple resume:

- Clear sections and white space.

- Lead with a 2-sentence profile summary.

- List out experience in reverse chronological order.

- Under each ‘experience’ section, simply describe what you did in language that makes sense to a non-expert. You may be tempted to use language that conveys how intricate and complex your contributions were, but the main thing they actually need to contain is something quantifiable.

- How many projects did you run? How many students did you supervise? How many participants’ data did you analyze? These are all meaningful markers of the work you’ve done, but don’t require the reader to be an academic to understand them.

- The bullet points themselves should be tailored to the job you’re trying to get. They need to have an easily-translatable application to the job you’re applying for. Mention experimentation, hypothesis testing, statistical analyses and modeling you’ve done - apply different weights to these skills depending on the job.

- Technical skills in list format. Don’t be tempted into using scoring systems describing your relative expertise - it’s arbitrary and not machine readable.

- Yes, your talks and publications are impressive. No, you can’t keep them itemized on your resume. At least not all of them. You can list the number of talks/papers or a few titles you’re especially proud of, but keep it concise.

- (This advice doesn’t apply if you’re going for research scientist or purer ML/AI roles - publications in broadly recognized journals should be in a separate section higher up.)

I would also highly recommend having some sort of a website with a portfolio you can share with people. It can just be your github profile, that’s fine. But it helps to show you can do the job in absence of prior experience actually doing the job.

Part 3: Upskill

Excellent companies will understand that the main thing PhDs are really good at is learning things on the fly and making connections between observations, and will filter for specific technical skills less strictly. However, in a capitalist society your labor has to result in value for the company sooner rather than later, so there are precious few companies that will let you gradually learn the ropes. You generally have to hit the ground running and figure it out as you go. You can help yourself, however, by actually learning some stuff before or while you’re applying for jobs. This is a great, detailed post on the data science skillset.

Let’s return to the task of reading job listings. I recommend keeping track of skills and technologies that come up repeatedly in job listings you find interesting. You will never satisfy 100% of the bulletpoints, and that’s okay. But you need to figure out which of the skills you don’t yet have are dealbreakers.

In general, job descriptions are written in reverse order of importance. So if you really want a particular job that’s ostensibly in data science, and the first skill listed is ‘building sophisticated machine learning models in Tensorflow’ and you’ve never touched ML, this is probably not the job for you. Yet. It’s good information to have though and you can definitely get there if you really want to.

Here’s my list of things I wish I had learned better before even starting my search:

- SQL. It’s a must. I still don’t love it. I took a free course (there are lots) just to get an understanding. DataLemur’s tutorials are also fantastic - as are their practice questions.

- Git. I had a couple of github repos, but I was always the only contributor so things like resolving merge conflicts, rebasing, and switching between branches were new and confusing to me. If you haven’t already, it’s worth at least setting up a repo, creating a branch, then merging it in - just so you get a feel for the logic of it. Here’s a guide I like.

- Having a bit of a sense of how platforms like AWS and GCP actually work is invaluable because they’re so ubiquitous. I kind of just learned it as I went, but in hindsight I wish I had read up on cloud platforms. Bonus: This will also make it way easier to talk to your data engineering colleagues.

- Software development best practices. I could do jupyter notebooks and long R scripts just fine, but actually building out a codebase was alien to me. It’s worth putting some effort into learning modularization principles. It makes productionalizing anything you do so much easier you’ll feel stupid not having done it ages ago (ask me how I know).

The good news is these things are actually best learned by just building something - which, incidentally, can be shown in your portfolio. Build a project with a codebase made up of modules instead of throwing everything into a notebook. Make a little project with flask. Once the logic clicks, there’s no going back.

You also have to become more agile and more willing to just try things and deliver results on shorter cycles. It feels very painful at first, but you can flex that muscle. My recommendation would be to try taking a Kaggle dataset and set a timer for yourself: how many insights can you pull from it in an hour? In two? In a day’s work? You probably won’t manage to build a super-sophisticated algorithm, but one thing I have learned is that employers are wary of former academics because we are slow. Think about the minimal valuable results you’ve delivered as a scientist. How fast can you get your finger on the pulse regarding whether something is working or not?

(This advice again doesn’t really apply to research scientist roles - you will most likely have the benefit of time since your output requires deep thinking and evaluation. I’m talking about the average data science role.)

Part 4: Apply, rinse and repeat

In terms of the search itself, things may take a while, or interviews might happen for you right away. Data science has become a bit saturated, and you’re up against people with existing industry experience, or grads from data science programs. So you need to be patient if things don’t start happening right away. Think about ways you could further tweak your resume, but don’t obsess over it. Look at it with a very critical eye for academic jargon - is there anything else you could make more accessible? I experienced a real step function with one particular tweak in my resume.

Beyond that, it’s a numbers game. I don’t subscribe to the ‘apply to everything’ school of thought - what felt doable to me was indexing heavily on the mental filters, applying to roles that truly seemed like a good fit, and occasionally firing off an application to a sub-perfect fit role without expecting to hear back (and then sometimes you do!). The number of applications you should be submitting depends on how picky you are, how well suited you are to these roles, and how much time you have - there’s no hard and fast rule.

I’d recommend joining any Slack groups that might exist for data science/ML/R/Python in your city/area. Typically they’ll have an #opportunities channel and you may even be able to chat with the hiring manager directly. In addition to LinkedIn, other websites I’ve found helpful for narrowing down my search were TrueUp and the Welcome to the Jungle app which matches jobs to your skills/preferences. There are tons more, these are just examples. Always apply through the company website though - these sites can sometimes have stale postings so verify it’s actually still live.

Part 5: Finding meaning post academia

The main existential thing you might be thinking is “but will I find the work meaningful?” The answer is, maybe. It almost definitely won’t be as deeply intertwined with your psyche as your academic research was. The real lesson is to let go of your identity as an academic. Your experience is valuable, pursuing the academic journey was not a waste, and the company that eventually hires you will have made the right choice. But there are extremely few places where you’ll be able to follow your own ideas wherever they take you and answer your own questions - that’s the freedom academia affords.

This might feel like a dealbreaker - and maybe it is. If you truly can’t fathom the idea of working on someone else’s problems interesting, you probably need to do some more soul searching. I will say, though, that it feels remarkably easy to find things interesting if you just let yourself be curious. A beautiful symbiosis can flourish between things you’re interested in, things you’re good at, and things that are valuable to your company. I recognize that I’m in the privileged position of running out of my own ideas first, but I promise you, it can be really fun and you end up meeting people from all sorts of backgrounds and learning about things you didn’t even know existed. You won’t learn if you don’t try.